|

Those of us who write and work on social work and social welfare history do so because it provides a sense of wonder and discovery

and imagination. Finding historical evidence is a form of truth-telling, of setting the record straight. It enables one to

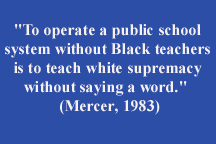

correct myths and fallacies. It allows one to speak truth to power. Learning and teaching about "other" histories

allows one to amend overt and tacit notions about a profession's history, personalities and events.

This article briefly identifies some "lost" social work pioneers of color who practiced before the Modern Civil

Rights Movement. Many of these men and women helped to shape the professional practice of social work in their local communities

and at state or national levels. They led agencies or delivered services during legalized racial segregation and before

New Deal legislation. Before, during and after the Great Depression, they had to deal with clients and constituents who often

existed on the economic margins while at the same time operate in a "race denying" social and political environment.

Despite all we could learn from their leadership and courage, today these pioneers are seldom mentioned or acknowledged.

They have become "lost" or obscure for a variety of reasons, including omission from the mainstream professional

literature and educational enterprises. Yet, their lives, professional experiences and contributions are instructive for

social workers today.

In the past fifteen years we have seen heightened interest and actions to include new actors and contributors of color

to the knowledge base of the profession. Social work scholars have created fascinating bodies of work on early African American

pioneers in the social work and social welfare (See Carlton La Ney,1994,2001; Peebles-Wilkins, 1995; Gary and Gary, 1977;

1994; Chandler, 2001). New social work scholarship is emerging on influential educators and organizational leaders like Forrester

B. Washington and Eugene Kinckle Jones. (Barrow, 2001; Armfield, 1999)

Educators like Joyce Z. White (2001) add to our knowledge of First Nations people. The National Association of Social

Work provides a website entitled "Brief Notes on Latino/Hispanic Contributions to Social Work History." Seven activists

and social change agents of Latin descent are described. NASW News profiles a social worker of color during various heritage

months. The National Association of Black Social Worker's website has a useful bibliography on African American social work

history. "Milestones of Asian American Experiences and Social Work Practice" is a fascinating document and timeline

on events, legislations and circumstances confronting Asians Americans from 1790 to 1997. (Sung, 1999).

For social work educators, cursory content on pioneer African American social workers can be found in several places.

Modern introductory social work texts mention early African American personalities like Ida B. Wells-Barnett and George Edmund

Haynes and organizations, like the National Urban League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

The Encyclopedia of Social Work (1995) offers biographical information on thirty major social welfare leaders ranging from

Sojourner Truth to Whitney Young. While all the above references are noteworthy and a "beginning", they represent

a thimble of the full range of "documented" historical figures of color in social work.

Several points are important here. First, there is a growing body of literature, scholarship and resources on African

American social work pioneers that spans from colonial times to today. Equally important are the emerging works on social

work pioneers of Latino, Asian and American Indian descent. The belief that they do not exist or did not contribute is a false

one. When key persons of color are absent or portrayed as recipients/objects of services only, the distortion of the history

of social work and social welfare continues.

Secondly, finding their voices, experiences and contributions requires the dedication of a sleuth. But once documents

are found, these amazing professionals teach lessons about empowerment, social justice and service that are relevant for today.

Finally, BSW educators and programs can make a contribution to the profession by unearthing, documenting and teaching

about social work pioneers of color in their state. Social work history is more than a national history that began out of

Hull House. Every state has social work pioneers. Social work practice, service delivery and education have state, regional

and local histories. State and local history of the profession holds fascinating insights on the maturation of careers, agencies

and treatment of various population groups. Unfortunately, this level of social work history is seldom examined or taught.

Bringing these pioneers out of obscurity is important social work practice and research!

|